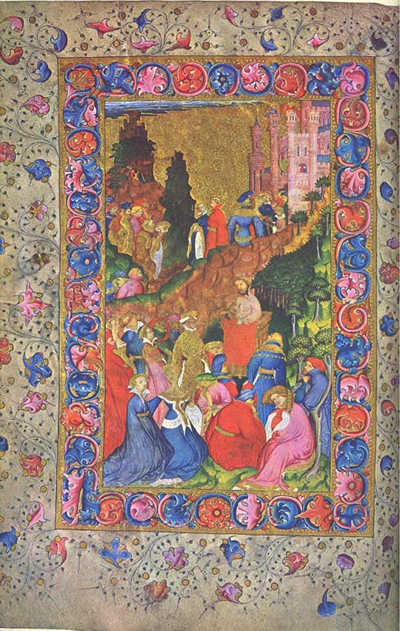

Geoffrey Chaucer giving a reading his Troilus and Criseyde to a courtly audience

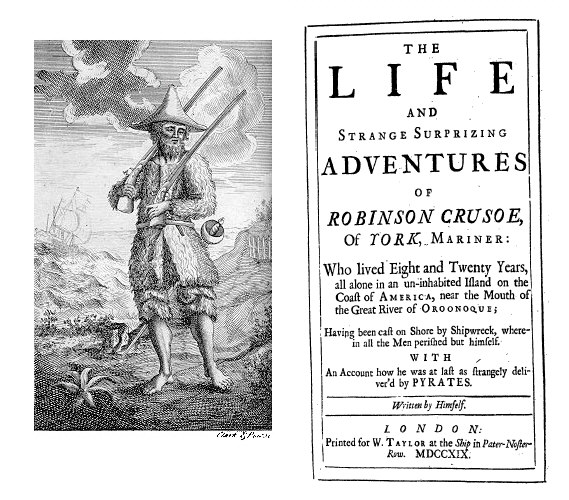

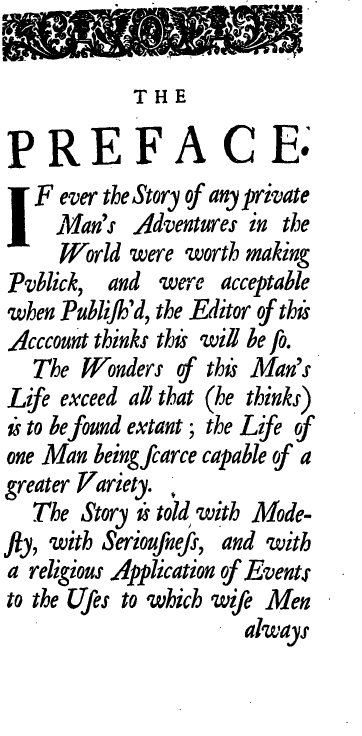

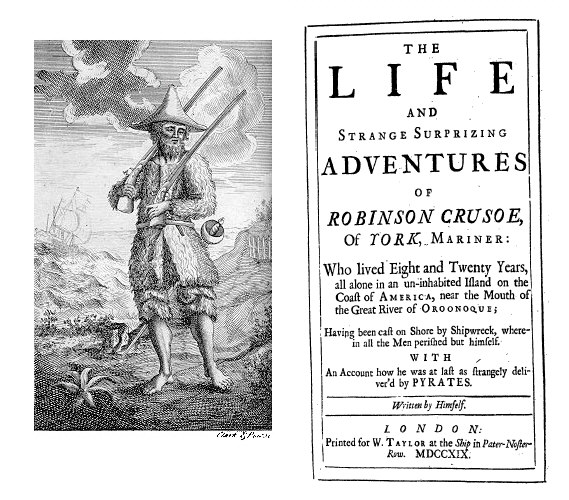

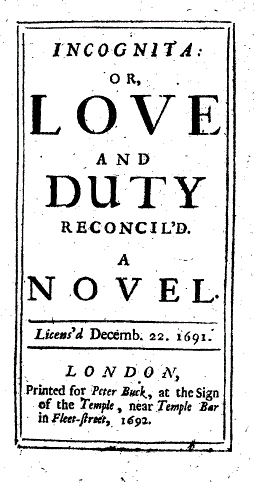

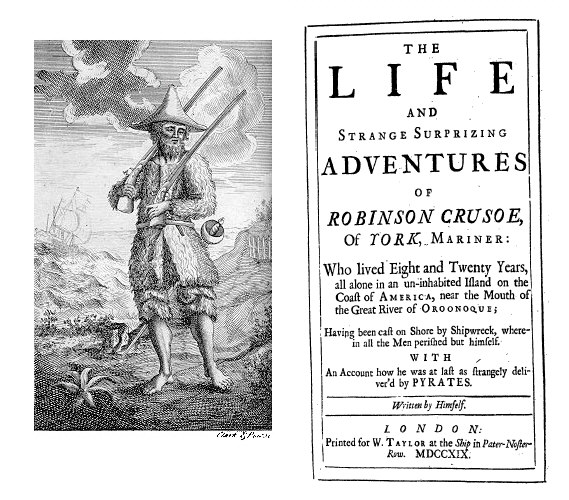

the first edition, frontispiece + title page: 5 shillings

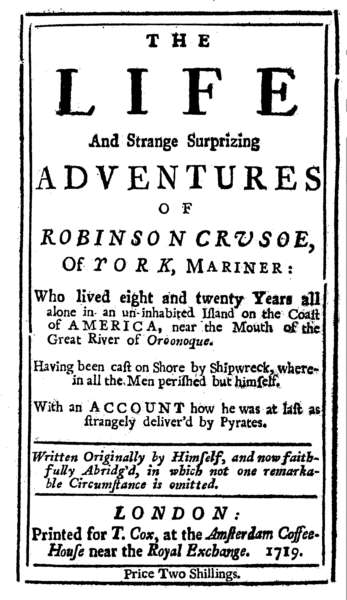

the first piracy: 2 shillings

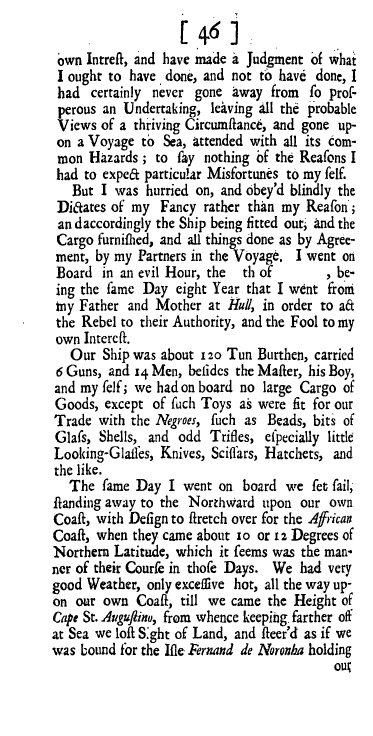

|

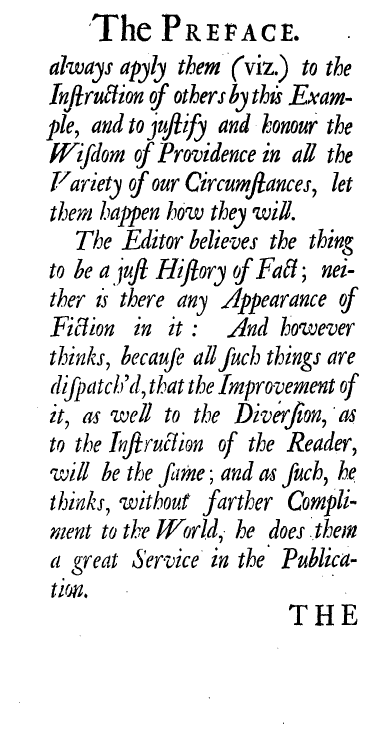

|

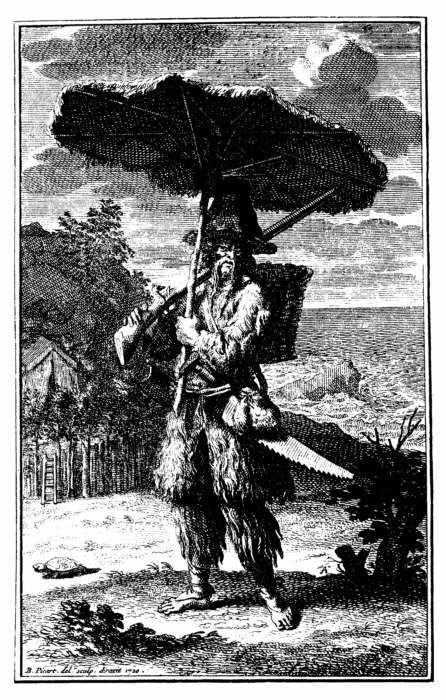

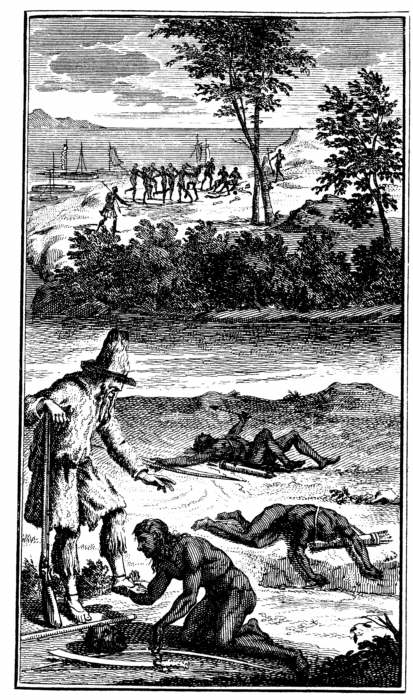

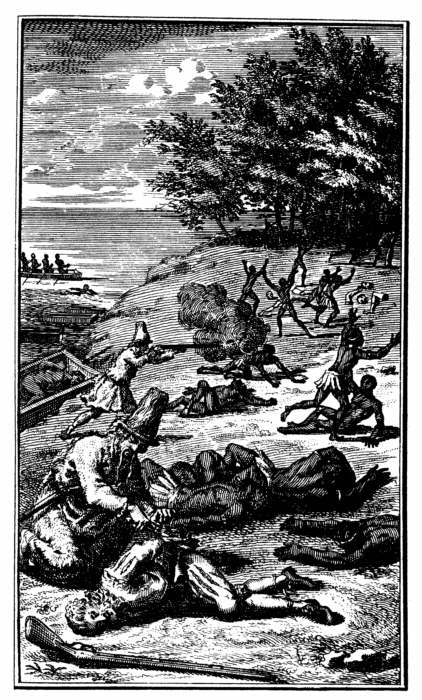

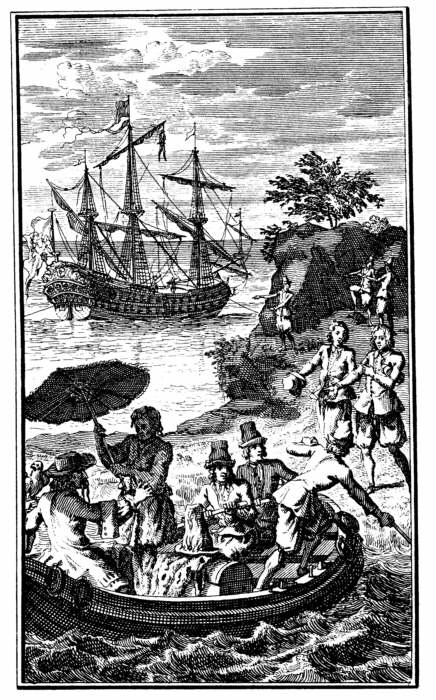

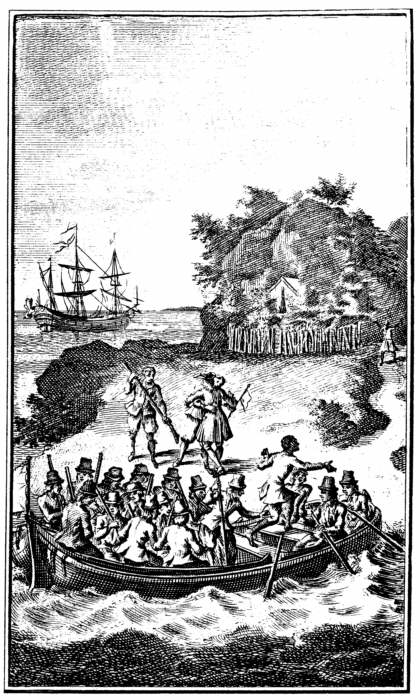

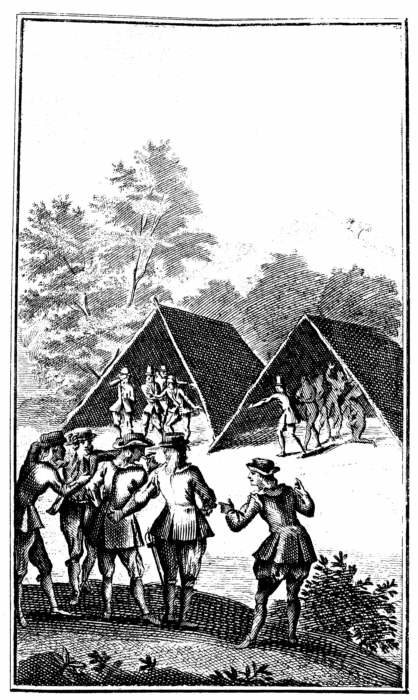

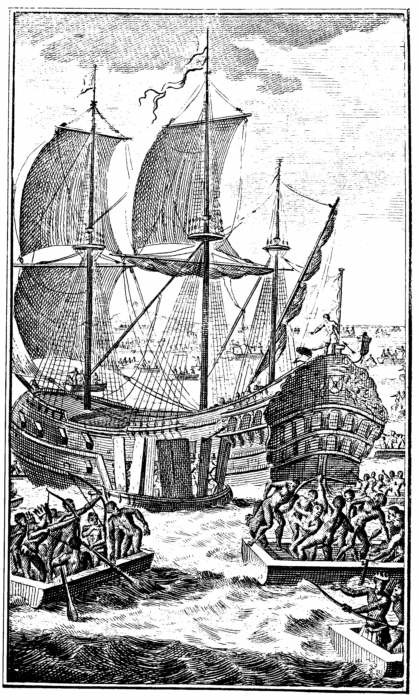

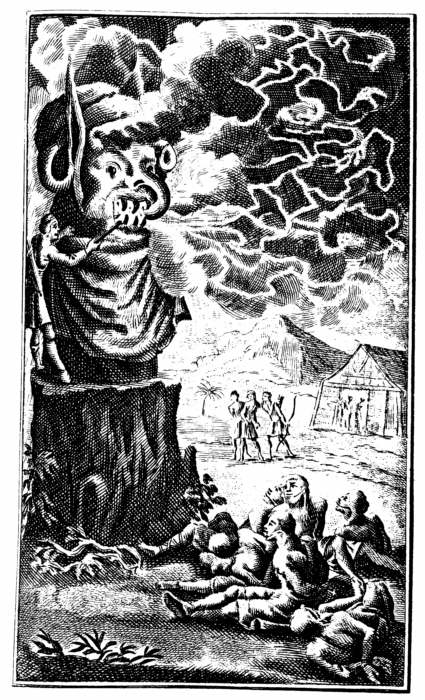

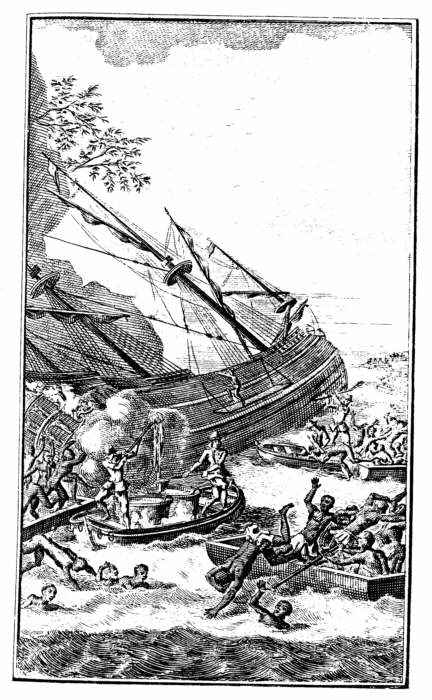

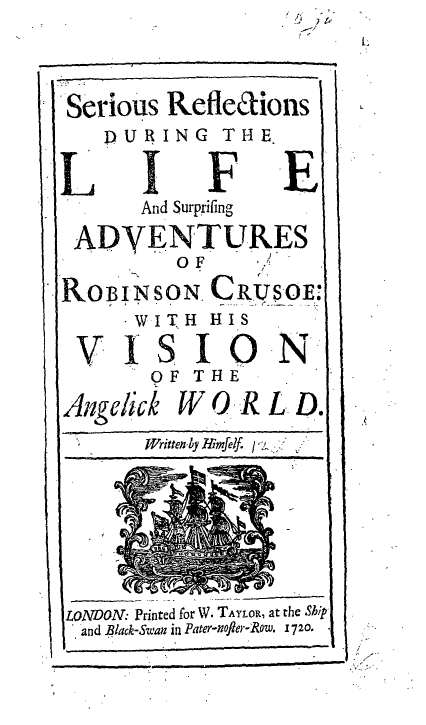

A 1720s chap book edition: all three volumes with wood cuts

|

|

|

|

|

|

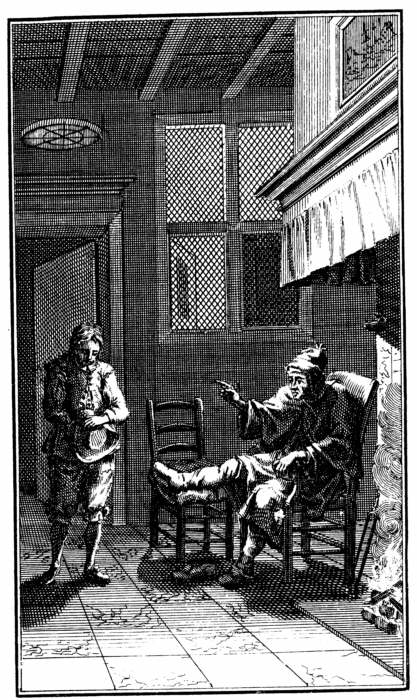

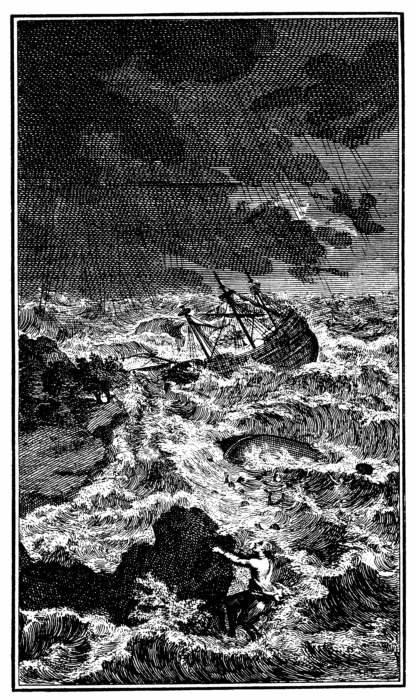

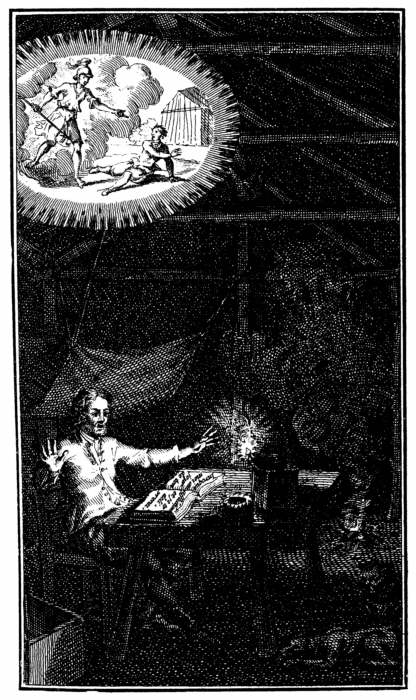

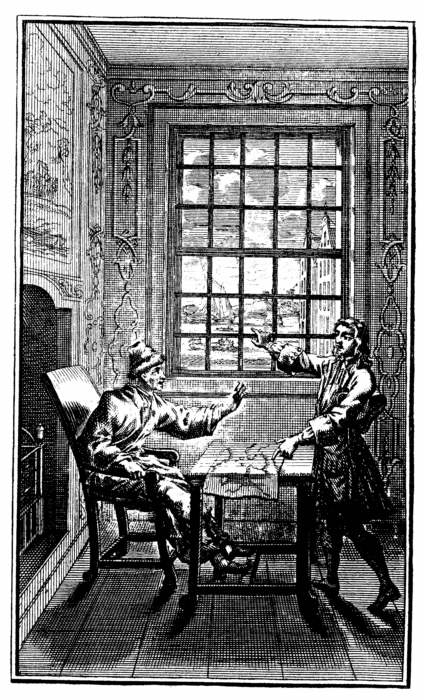

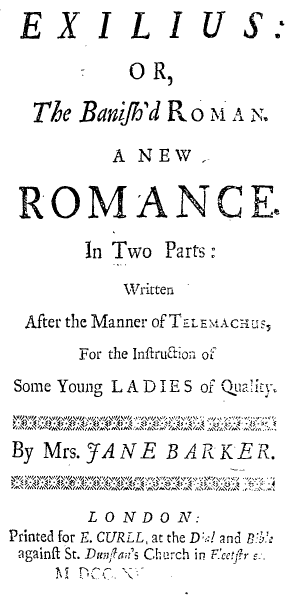

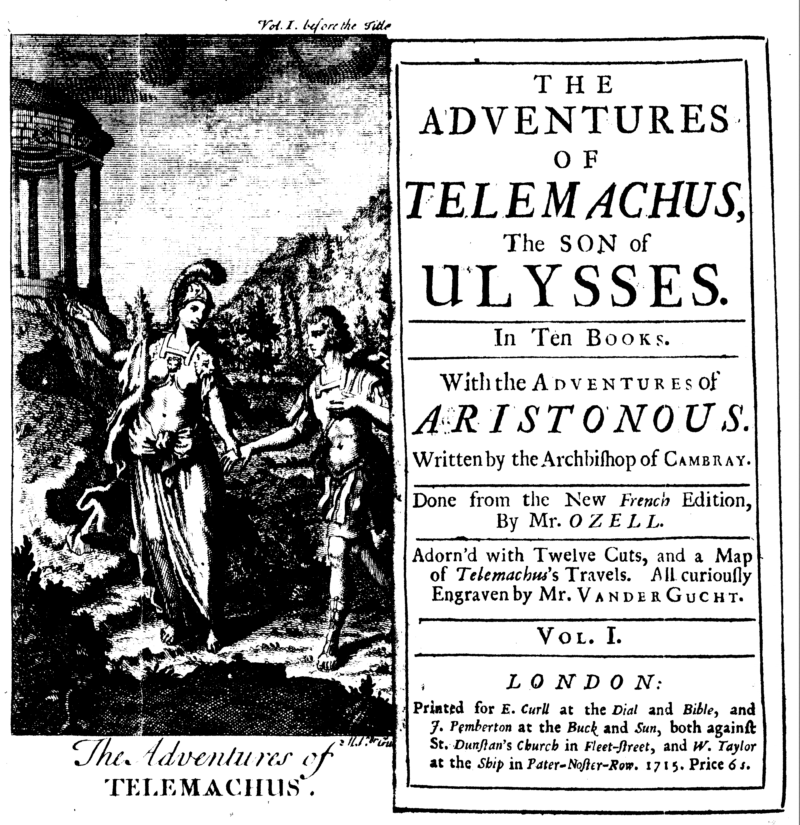

| François Fénelon, Telemachus (London: E. Curll, 1715) | Daniel Defoe, Robinson Crusoe (London: W. Taylor, 1719) |

| 3.1 Heroical Romances: Fénelon's Telemach (1699) |

||||

| 1 Sold as romantic inventions, read as true histories of public affairs: Manley's New Atalantis (1709) |

2 Sold as romantic inventions, read as true histories of private affairs: Menantes' Satyrischer Roman (1706) |

3.2 Classics of the novel from the Arabian Nights to M. de La Fayette's Princesse de Clèves (1678) |

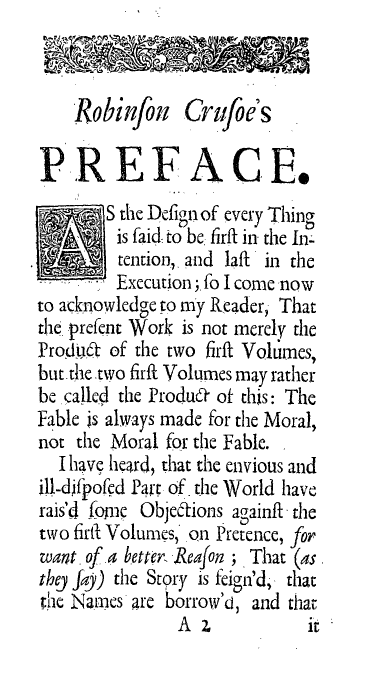

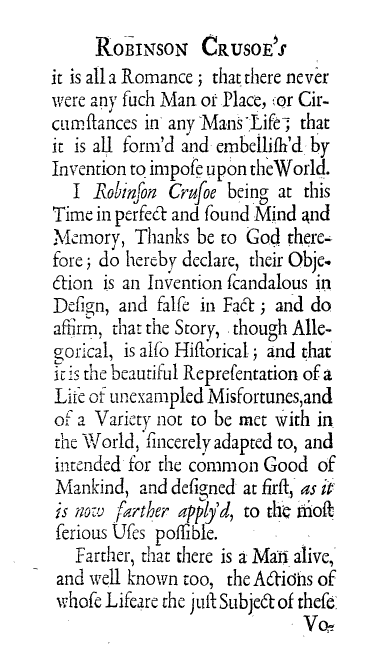

4 Sold as true private history, risking to be read as romantic invention: Defoe's Robinson Crusoe (1719) |

5 Sold as true public history, risking to be read as romantic invention: La Guerre d'Espagne (1707) |

| 3.3 Satirical Romances: Cervantes' Don Quixote (1605) |